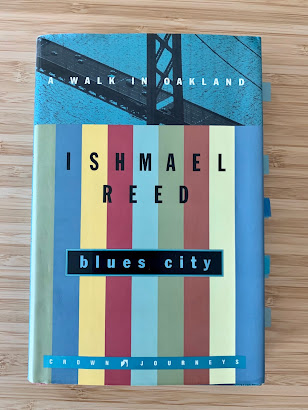

Black History Book Review: Ishmael Reed’s Blues City

A finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and nominee for the National Book Award, Reed is an American writer best known worldwide for his 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo, set in the 1920s during the Harlem Renaissance. Mumbo Jumbo has been in print continuously, translated into French, Italian, Spanish, and even Japanese (plus a Chinese version currently in the works). Reed was also a professor who taught at universities on both the East and West Coasts throughout his career, including Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, and finally UC Berkeley.

Blues City is a unique autobiographical work. It is a blend of local/urban history and the author’s reflections on the political and cultural life of the city of Oakland, California (mediated through a series of walking tours he takes through different neighborhoods). The “blues” in the title is a reference to the legacy of blues music in Oakland. One musician who Reed interviews in the book explains that when Black Americans migrated from the South during World War II to work in West Coast shipyards, “they brought their instruments with them.”

Before the East Bay became absorbed into the economic sphere of Silicon Valley technology companies, it was best-known as a hub of activism and social justice that captivated the nation and the world. Reed, who first moved to Oakland in 1979, grounds readers in the rise and fall of Black Power in the city. The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland in 1966 and it plays a central role in the story Reed tells about the city (read more about the Panthers in my first blog post).

Pushing against an incomplete narrative of the Panthers, Reed shows that their local contributions through their community work have gone unacknowledged by the city. Oakland earned a place as a household name for the Black freedom struggle. Reed makes the case that memorialization through monuments is long overdue (fortunately, the Huey P. Newton Foundation is hoping to change that).

Blues City gives us the history to appreciate the roots of displacement of Black residents today. A strong theme in the book is the tug-of-war between preservationists and long-term residents’ interests on one hand and the winds of economic and social change on the other hand in a gentrifying city. As Reed explains, "from the seventies through the nineties, there was a black mayor, a black symphony conductor, a black museum head, black members of the black city council…[and] Mayor Lionel Wilson, whom the Panthers wanted to lead a nationalist surge...and other black elected officials openly attributed their electoral success to support from the Black Panther Party."

Several Black community leaders, including David Hilliard, a former Black Panther interviewed by Reed, gradually transitioned from support to disillusionment when it came to Jerry Brown. Brown, a white Oakland mayor, initially received the support of the Panthers during his campaign. During his 1999 mayoral election, the endorsement of the Black Panthers was so strong that Reed attests that one campaign event “resembled a Black Panther Party reunion.” However, once in office, Brown lost a degree of popular support as he strayed from promises for affordable housing and employment. Many Black Oaklanders did not reap the benefits of initiatives for economic development in their city and lost faith in Brown over the years.

My hardcover edition of Blues City included a map of downtown Oakland in the beginning, which proved to be quite helpful as the book takes you time-traveling through Oakland’s streets and landmarks. Reed makes several specific references to street names and intersections throughout the book! The map includes Lake Merritt, which Reed explains as often thought of as the “jewel” of the city. I would add that the Lake is also the heart of Oakland, notable not only for its beauty but its centrality to the cultural life of the East Bay community. Family outings, birthday parties, and protests for the Black Lives Matter movement all take place alongside the Lake.

Blues City is essentially a guided tour of Oakland in book form, enticing for both Bay Area natives and newcomers alike. In-person guided tours might not be possible during the pandemic, but Oakland residents can still take pleasure in reading a chapter and taking a solitary yet meditative walk through one of the city’s neighborhoods. The book is also an easy read and the reflections come off like an intimate oral history with a family member or neighbor. In conclusion, this is definitely required reading for those interested in the Black history of Oakland. Moreover, Reed does a fantastic job weaving in forgotten histories of Chinese, Latinx, and indigenous people whose families have called Oakland home for generations.

The African American Museum and Library at Oakland (AAMLO) makes a few appearances throughout Blues City so it was a great book to read during my research fellowship there. As part of my work with the museum this summer, I compiled a comprehensive list of the institution’s library holdings related to the history of Oakland and the Black Panther Party. Blues City is included, along with several other nonfiction and fiction books. I wrote about this online resource in an earlier post this month.

I hope to review more books from AAMLO’s collection in the months to come. Stay tuned and thanks for reading!

Comments

Post a Comment